|

Benedictines, Cistercians,

Trappists, and Carthusians |

|||||

Stanley Roseman

The MONASTIC LIFE

The MONASTIC LIFE

The FOUR MONASTIC ORDERS of the WESTERN CHURCH

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

The Artist and The Trappists

Page 4 - Trappists Continued

On the bottom of this page are links

to the other pages on the Monastic Orders.

On the bottom of this page are links

to the other pages on the Monastic Orders.

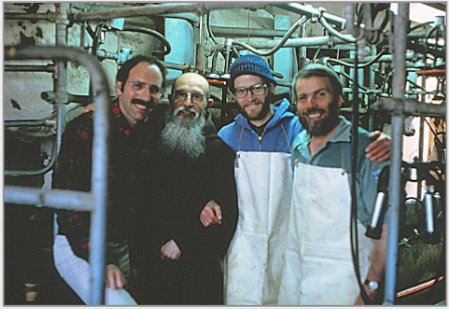

Stanley Roseman (left), Frère Élie, Frère Michel, and Frère Samuel (right), manager of the dairy farm at the Abbey of La Trappe, Normandy, spring 1979.

The Abbey of La Trappe - Fountainhead of Trappist Monasticism

Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis made their first sojourn at the Abbey of La Trappe, in Normandy, in early June 1979. La Trappe gives its name to the branch of Cistercian monasticism that developed from a seventeenth-century spiritual movement of rigorous asceticism centered at the Abbey. In the late nineteenth century, the growing number of monasteries that followed the Trappist regime joined together to form a separate order which acquired the name Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, also known as the Trappist Order.

Standing next to the artist in the photograph above is Frère Élie, whose letter of invitation says that with "great pleasure'' the two friends will be received at La Trappe. Roseman relates: "Ronald, who had been writing the letters on our behalf to explain the nature of our request for a visit, received a warm letter of invitation signed by Frère Élie, the Doorkeeper. That was the first time we had received a letter of invitation from the porter of a monastery. Ronald and I appreciated the sense of monastic history attached to such a letter for the Rule of St. Benedict dedicates a chapter (Chapter 66) to the porter of the monastery and counsels that at the monastery gate should be a wise man of years who knows how to receive and give messages." (See the drawing Frère Élie at Vespers and letters from the Trappist monk on the page "Correspondence from the Monasteries.")

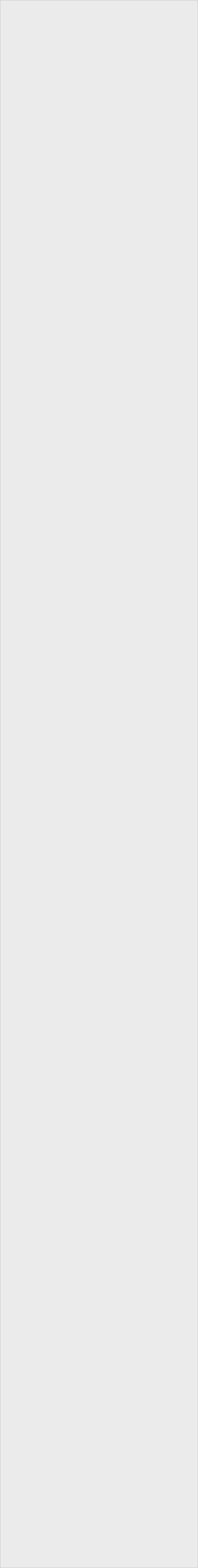

"The warm welcome and gracious hospitality we received from Abbot Gérard Dubois and the Community and the great encouragement given Ronald and me in our work meant very much to us," writes Roseman, who was brought inside the cloister to draw the monks. Presented below, (fig. 2), is a portrait drawing of Brother Samuel. After the Trappist monk's morning work on the farm, he thoughtfully sat for the artist in the scriptorium.

In this impressive portrait Frère Samuel, vigorous strokes of black and bistre chalks delineate the monk's strong, facial features. The beige paper imbues the composition with a warm tonality. Passages of black chalk describe the monk's dark hair, moustache, and beard, and accents of white chalk add heightening to the skin tones. Roseman has effectively expressed an asceticism in the portrait of Frère Samuel, who had dedicated years of manual labor on the Abbey's large dairy farm as well as having maintained the rigorous regime of the Trappist Order.

The eminent American collector John Davis Hatch, Cofounder and first Director of Master Drawings Association, acquired the portrait Frère Samuel; a drawing from the Trappist Abbey of San Pedro de Cardeña, in Castile; and a drawing from the Benedictine Abbey of Fleury, along the River Loire. In letter to Ronald Davis, who brought Roseman's drawings to the attention of the collector, John Davis Hatch enthuses, "they are great additions to my drawing collection.''

2. Frère Samuel, 1979

Abbaye de La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

John Davis Hatch Collection

Abbaye de La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

John Davis Hatch Collection

© Stanley Roseman

Frère Samuel's friendship with Roseman and Davis continued for more than twenty years through their subsequent returns to La Trappe. (See the oil on canvas portraits from 2002 of Frère Samuel, (fig. 9, below), and on the page "Monastic Journey Continued - A Painting Studio at the Abbey of La Trappe.")

Frère Samuel thoughtfully brought Roseman and his colleague Ronald Davis on a tour of the abbey farm, following which Davis took the photograph presented here of the artist and the Trappists.

Roseman is asked to give a Talk on his Art to the Monks

Abbot Gérard asked Roseman if he would give a talk on his work to the Community and show slides that Davis had brought with them of the artist's paintings and drawings on a variety of subjects. Roseman had been asked to speak about his work in a number of monasteries where he and Davis had sojourned.

The artist writes in his journal: "Abbot Gérard thoughtfully rearranged the daily schedule. After Mass, the monks gathered in a room where seats and a slide projector and screen had been provided for the occasion. Ronald and I had selected drawings to show from the preceding days' work. As I did not speak French fluently, I spoke in English and Frère Élie kindly translated my talk to the Community."

"I was honored to be invited to speak about my work to the monks of La Trappe," writes Roseman in his journal, "and I was sincerely appreciative for their enthusiasm for all my work. I said to the Community that being given this wonderful opportunity to draw at La Trappe, fountainhead of Trappist monasticism, was greatly meaningful to my work on the monastic life, and I expressed to Abbot Gérard and the monks my deep gratitude.''

Roseman spoke about drawing at opera, theatre, and dance productions in the United States and drawing and painting portraits of the clowns at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. The artist showed slides of work that comprised the exhibition Stanley Roseman - the Performing Arts in America, produced by Davis for the American bicentennial. Roseman spoke about traveling with Davis in 1976 to Lappland, where the artist painted portraits of the nomadic Saami people, and the exhibition the following year at the Peabody Museum, Yale University. The artist's slide presentation and talk concluded with his current work on the monastic life.

The interest and appreciation that the monks expressed for the different subjects in the artist's oeuvre were reaffirmed by the Parisian daily La Croix in an article published later that year on Roseman and his work:

"He found again in the hospitality of the monasteries what he found in the Saami camps and under the circus tents. Is there not a profound relationship between the migrations of nomads, the voyages of traveling players, and the inner journey which is the contemplative life."

- La Croix, Paris

A History of the Abbey of La Trappe

During the 1980's, Roseman was much engaged in writing a text to accompany his paintings and drawings on the monastic life.[1] In Roseman's return to La Trappe, Abbot Gérard thoughtfully made the library available to the artist for his ongoing research and study, and several monks kindly assisted him with information on the Abbey and on Trappist monasticism.

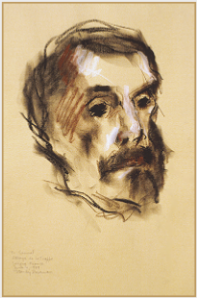

"The Abbey of La Trappe, in the Department of the Orne, in Normandy, traces its history from 1122, at a place called La Trappe where a chapel was built by Comte Rotrou III du Perche in memory of his deceased wife Mathilde, granddaughter of William the Conqueror. In 1140, monks from the nearby Abbey of Breuil-Benoît, in the Benedictine Congregation of Savigny, began a monastic community at La Trappe.[2] Seven years later, during a century of great expansion of Cistercian monasticism throughout Europe, the Congregation of Savigny joined the Cistercian Order, which dates from the founding of the Abbey of Cîteaux, in Burgundy, in 1098.

"The observance of monastic life at the Abbey of La Trappe in the seventeenth century had a profound influence on the development of Cistercian monasticism.

"Armand-Jean Le Bouthillier de Rancé, born in 1626 of an aristocratic family, pursued an ecclesiastical career as his family had intended for him. However, in his thirties, Rancé felt a calling to the contemplative life. After a few years of reflection, which included a visit to La Trappe in the summer of 1658, he divested himself of his properties and benefices; received royal permission to transfer his hereditary title of commendatory abbot of La Trappe to that of regular abbot; entered the novitiate at the Abbey of Perseigne, near Alençon; and, after a year, made his monastic profession. In 1664, Rancé returned to La Trappe.[3]

"Inspired by accounts of early monastic life in the deserts of Egypt and Syria, Abbot Rancé established a rigorous spiritual asceticism at La Trappe. The monks devoted long hours to personal prayer and meditation, in addition to the communal worship in choir; maintained an abstemious diet with fasting; and practiced self-denial; penance; and strict silence.

"The rigorous regime at La Trappe was taken up by other Cistercian abbeys in Europe. More Trappist monasteries were founded in the nineteenth century, including several in the United States. An independent branch of the Cistercian Order was established at a special chapter of the Trappist congregations held in Rome in 1892. The 'old' order, comprising those Cistercian monasteries that remained apart from the Trappist congregations, became known as the Order of Cistercians of the Common Observance. The Trappist congregations that formed a separate order acquired the name Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, familiarly called the Trappist Order."[4]

Returning to the Abbey of La Trappe, 1982

3. The Abbey of La Trappe from an eighteenth-century engraving.

Courtesy of the Abbey of La Trappe

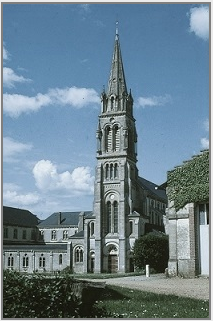

4. The present-day abbey church, built in the nineteenth century.

In Roseman's text, from which are excerpts below, the artist speaks about the history of the Abbey of La Trappe and the establishment of the Trappist Order.

Roseman and Davis, who had kept in correspondence with the monastery through Frère Élie, received a cordial letter from their friend in autumn of 1982: The monk writes: "I read with pleasure that you intend to visit La Trappe again in the near future. All of us will welcome you heartily and in the meantime send you our very best wishes. Affectionately, Frère Élie."

1982 brought Roseman and Davis to monasteries in Switzerland, in February and March; Italy, in June; and Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands, in July. In August and later that year, in November and early December, the artist and his colleague returned to monasteries in Germany.

Vigils

7. Père Robert at Vigils, 1982

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Albertina, Vienna

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Albertina, Vienna

Page 4 - Trappists Continued

The Biblical call to pray to God in the night is stated by the Prophet in the Book of Psalms: "At midnight I rise to praise you, O Lord.''[5] (Ps. 119:62)

"The Lives of the Desert Fathers (Historia Monachorum in Aegypto), a fourth-century contemporary account of Christian monks and hermits living in the Egyptian desert, records the vigils kept by those pious men.[8]

"St. Benedict in his Rule allocates five chapters to the Night Office: Chapters 8 and 9, on the Divine Office at night and on the number of Psalms for the Night Office; Chapter 10, on Vigils in summer; Chapter 11, on Vigils on Sundays; and Chapter 14, prescribes the Psalms for the Night Office for the feasts of the saints.''

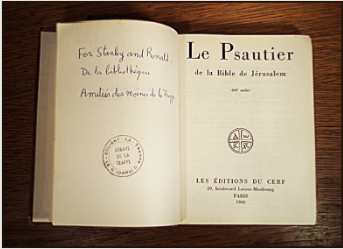

6. Title page of the Book of Psalms.

A gift copy of the Book of Psalms given in friendship from the monks of the Abbey of La Trappe to Stanley Roseman, of the Jewish faith; and Ronald Davis, of the Roman Catholic faith.

The Monastic Life and the Rule of Silence

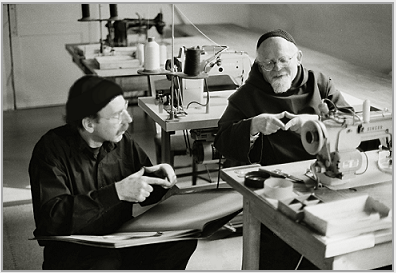

8. Père Robert, the tailor, (right), teaching Stanley Roseman Cistercian sign language in the tailor shop

at the Abbey of La Trappe, 1998.

at the Abbey of La Trappe, 1998.

In the photograph, the Trappist monk is showing the artist the sign for the word "bread."

The Development of Sign Language in Monasteries

"The introduction of a fixed system of gestural language is credited by scholars to the Abbey of Cluny, in Burgundy, under the Benedictine monastery's second abbot, St. Odo (926-942).[12] A century later, several monks compiled lists of signs, as did Bernard of Cluny, who in 1068 enumerated 296 signs. Udalricus, also a monk of Cluny, compiled a list of signs of which many show similarities to the sign language that later developed in Cistercian monasteries. By way of example is the sign for 'bread,' which is indicated by touching the tips of the forefingers and thumbs of both hands in a triangular configuration. . . ."[13], (fig. 8).

Meditation and Prayer

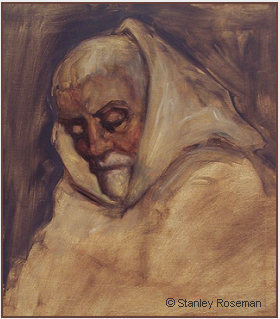

9. Frère Samuel,

Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Prayer, 2002

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Oil on canvas, 60 x 60 cm

Private collection, France

Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Prayer, 2002

Abbey of La Trappe, France

Oil on canvas, 60 x 60 cm

Private collection, France

"The Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 48, entitled 'The Daily Manual Labor,' instructs that the monks be engaged in work during prescribed times of the day as a balance to the hours devoted to prayer. Trappists emphasize manual labor in their interpretation of the monastic precept ora et labora, prayer and work.

© Photo Ronald Davis

© Photo Ronald Davis

© Stanley Roseman

"In my reading and study on the monastic life,'' the artist recounts, "I learned that the Night Office observed in monasteries today has an ancient precedent in Judeo-Christian early monastic traditions in the Middle East. The desert settlement of Qumran, near the Dead Sea, was a center of monastic life in Judaism from the second century BC to the first century AD. The Dead Sea Scrolls include the Rule of the Community and accompanying texts that relate the communal life at Qumran: adherence to obedience, celibacy, and self-denial, the ritual of the common meal taken in silence, the daily round of worship with singing the Psalms, and the lengthy vigil in the night.[6]

"The Therapeutae, the subject of Philo of Alexandria's treatise The Contemplative Life, were Jewish eremites contemporary with the Qumran community. The Therapeutae, whose main settlement was near Alexandria, lived in solitude in hermitages and observed a strict regime of prayer and reading and studying the Holy Scriptures. On the Sabbath the hermits met in a sanctuary for a sermon given by an elder. Every seven weeks, as seven was regarded as a sacred number, the hermits assembled for a discourse and common meal followed by a vigil with prayers and singing until dawn.[7]

"For Stanley and Ronald,

De la bibliothèque

Amitiés des moines de La Trappe."

De la bibliothèque

Amitiés des moines de La Trappe."

Since early Christian monasticism, silence has been an essential element in a life of contemplation and prayer. Roseman writes: "The Lives of the Desert Fathers makes repeated mention of fourth-century monks' asceticism and discipline of keeping silent.[10] The Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 6, extols the virtues of silence. St. Benedict states: 'For speaking and teaching belong to the master; the disciple's part is to be silent and to listen.' Benedict prescribes a rule of silence in the refectory when the monks take their meals while they listen to the weekly reader, (Chapter 36); and after Compline, when strict silence is required until morning, (Chapter 42)."

Recounting his return to the Abbey of La Trappe in December 1982, Roseman writes: "As was my custom for drawing at Vigils in monasteries, I prepared my folios of drawing paper and box of chalks before I went to bed and set my alarm clock. At La Trappe, I rose at 3:15 A.M., washed, dressed - and being that it was December in Normandy - put on my parka, gathered my drawing materials, and went to the church.

At La Trappe, the conclusion of the communal worship at the Night Office is followed by personal prayer. Roseman further relates:

- Abbot Gérard Dubois

Abbot of La Trappe

Abbot of La Trappe

"Devote yourself often to prayer,'' instructs St. Benedict in Chapter 4 of his Rule. In addition to the communal worship at the Divine Office, Trappist monks are required to devote extensive time to personal prayer.

During their sojourn at La Trappe that December 1982, Roseman and Davis presented the monastery with a gift of the artist's drawings for which Abbot Gérard expressed his sincere appreciation. In a deeply moving letter to Stanley Roseman, who is of the Jewish faith, the revered Abbot of La Trappe writes:

"I thank you again for your good wishes and for the drawings that you have generously given us.

They will be symbols of the bond that unites us,

regardless of the differences of language, religion, and life-style.

But in the most profound essentials, we are as one.''

They will be symbols of the bond that unites us,

regardless of the differences of language, religion, and life-style.

But in the most profound essentials, we are as one.''

A Gift to the Monastery

© Photo

Ronald Davis

Ronald Davis

"I took a seat in one of the pews, opened my drawing book and box of chalks, selected a stick of chalk, and began drawing. In the dimly lit church, several monks stood or knelt in side chapels, others came to sit or kneel in the pews or choir stalls to pray and meditate. Despite the cold, it was inspiring to be there in the night with the monks, whose encouragement of my work on the monastic life meant very much to me.

"At the tolling of the monastery bell at 4:15 A.M., the monks came forth from the side chapels and nave of the church and in from the monastery and took their places in choir. When all had assembled, Abbot Gérard tapped his ring signaling the cantor to begin the invocation from the Psalms: 'Seigneur, ouvre mes lèvres,' ('Lord, open my lips,'). And the monks responded in unison, 'et ma bouche publiera ta louange' ('and my mouth shall proclaim your praise.')''[9]

On the morning of December 14th, Roseman and Davis departed St. Stephan's Abbey, in Augsburg, for the more than a thousand kilometer drive to the Abbey of La Trappe. En route they encountered a snowstorm which prolonged their journey. They stopped several times along the way to call Frère Élie at the gatehouse to report their progress and to express their concern that they would be unable to arrive before Compline. As Roseman recounts: "Frère Élie cautioned us to drive slowly and carefully in the snowstorm and kindly assured us that he would be at the gatehouse to receive us at whatever hour we arrive. He also told us that Frère Marc said he would wait up for us to bring us to our rooms and see us settled in."

When Roseman and Davis arrived at La Trappe about 10 P.M., Frère Élie opened the gates and heartily welcomed his friends. Roseman relates: "Frère Marc, a kind and caring guestmaster, had supper ready for us. I thanked him very much for his gracious hospitality. I said what I had said to Frère Élie - that Ronald and I were very happy to be back and how much I was looking forward to resuming my work. Frère Marc thoughtfully told me that the church was cold and to dress warmly, especially when I draw at the long Night Office."

In the present work, subdued white highlights on Frère Marc's face, eyeglasses, and forehead and the mise en page emphasizing perspective bring the figure forward in pictorial space. The Trappist monk humbly stands with his head inclined and eyes lowered. His confrere in choir, drawn in fluent lines and transparent tones of bistre chalk, leans forward, his right arm raised and his head upturned towards the altar. In this compelling composition, Roseman beautifully expresses the individuality of the two Trappist monks, each absorbed in prayer at the Night Office.

Frère Marc, the ascetic, bearded guestmaster, stands in the foreground of the superb drawing Two Trappist Monks at Vigils, 1982, (fig. 5). The monks wear voluminous, thick, woolen cowls with long sleeves that cover their arms and hands. The predominant use of bistre chalk, blended tonal passages of bistre and black chalks, and reserved areas of the gray paper imbue the drawing with a nocturnal quality, as in the related drawing from the artist's sojourn that December at the Abbey of La Trappe, Père Robert at Vigils, in the collection of the Albertina, Vienna, (fig. 7, below).

Roseman's drawings at the Night Office, or Vigils, comprise an important part of his work in the monasteries.

5. Two Trappist Monks at Vigils

1982, Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Michigan

1982, Abbey of La Trappe, France

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Private collection, Michigan

"In my studies," Roseman further relates, "I read that in fourth-century Egypt St. Pachomius (293-346), revered as the founder of cenobitic Christian monasticism, specifies in his Rule that signs be used at certain times to preserve the silence that is essential to monastic life.[11]

Père Robert at Vigils, 1982, (fig. 7), is also presented at the top of the preceding page "Cistercians and Trappists.'' This excellent drawing was acquired by the Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, containing a world-renowned collection of master drawings, and included in the Museum's exhibition in 1983 of Roseman's drawings. (See website page "Exhibition at the Albertina."

In this intimate portrait, calligraphic strokes and tonal passages of bistre chalk establish a pyramidal composition in the depiction of the figure. A complementary geometric leitmotif of circular shapes and forms defines the monk's round face, round-rimmed eyeglasses, skullcap, and voluminous sleeves.

Père Robert leans forward, his arms rest on the back of a pew, his hands tucked into the sleeves of his cowl. The rendering of light and shade in blended tones, or sfumato, of bistre and black chalks with subdued white highlights and the reserved areas of gray paper give the drawing a nocturnal ambiance. Roseman conveys a deep spirituality of the Trappist monk in prayer and meditation in the night.

Roseman recounts: "Frère Samuel, being in retirement in 2002 from his demanding work on the farm, generously gave of his time to sit for me in my studio at La Trappe.''

© Stanley Roseman

"The historic changes that resulted from the Second Vatican Council included reforms to the strict use of sign language in Trappist monasteries and took into consideration the human need for moderate, verbal communication within the context of monastic life.

"I am fortunate to know an older generation of Trappist monks for whom sign language was for many years their principle means of communication with one another. I am grateful to Père Robert, who kindly taught me words and phrases in Cistercian sign language during my sojourns at La Trappe. However, I am grateful for the changes resulting from Vatican II and making possible in Trappist monasticism the sharing of friendship through the spoken word, as with my longtime friendship with Père Robert.''

The librarian Frère Benoît, who kindly assisted the artist and his colleague in their research and study, inscribed the Psalter on behalf of the monks:

Roseman also drew Père Robert in the tailor shop, where as the artist recounts: "An immediate rapport was established between us when I mentioned to Père Robert that my paternal grandfather was a tailor in New York City."

"After the last Psalms were sung; the Psalters, closed; and the candles on the altar, extinguished, the monks remained for an additional half hour for personal prayer and meditation in the darkened church. Some of the monks dispersed from choir to the side chapels, while others went to sit on the benches in the rear of the church or in the pews. I closed my drawing book and box of chalks, placed them by my side, and like the monks, I immersed myself in meditation and prayer."

Frère Samuel, seen in the photograph at the top of the page and in the portrait from 1979, (fig. 2), is the subject of Roseman's drawings created over the years at the Divine Office and on occasions when the artist accompanied his friend back to choir to draw him in personal prayer and meditation.

The friendship between the Trappist monk and the artist, which began in the first year Roseman drew at La Trappe, was especially meaningful: Frère Samuel's family in Normandy had been close friends with a Jewish family. During the Second World War, Frère Samuel's father, a medical doctor, brought the Jewish family into his home and gave them refuge during the Occupation.

On his sojourn at La Trappe in 2002, Roseman had the wonderful opportunity to paint portraits of the monks. The Prior Père Hugues, who was greatly encouraging of the artist's work, thoughtfully appropriated for him a studio on the second floor of a building by the inner gate of the monastery courtyard. That spring, as well as on subsequent returns to La Trappe through Christmas, Roseman painted a series of magnificent portraits of the Trappist monks. (See page "Monastic Journey Continued - A Painting Studio at the Abbey of La Trappe.'')

The Bibliothèque Nationale de France commends Roseman for his "innate artistic talent"

and praises his work in monasteries as "profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life.''[14]

and praises his work in monasteries as "profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life.''[14]

© Photo Ronald Davis

1. The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and wrote in a gracious letter

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. L. Aubry, Abbaye de La Trappe, (Rouen: C.R.D.P, 1979), pp. 3, 4, 5.

3. L'Abbaye Notre Dame de la Grande-Trappe, authored anonymously by a monk of La Trappe (Orne: Montligeon, 1926), pp. 65, 76, 78.

4. Louis J. Lekai, The Cistercians, (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1977), pp. 188, 189.

5. Psalm 119 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 118 in the Vulgate.

6. Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1962), The Community Rule, pp. 97-123.

7. Philo of Alexandria, The Contemplative Life and selected writings, translation by David Winston, (Paulist Press, New York, 1981), pp. 41-57.

8. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, translated by Norman Russell, (Oxford: Mowbray, and Michigan: Cistercian Studies, 1980), pp. 111, 112, 134.

9. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the Vulgate Bible numbering of the Psalms.

10. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, pp. 3, 65, 106, 114, 115, 149, 155.

11. Robert A. Barakat, Cistercian Sign Language, (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1975), p. 24.

12. Lekai, The Cistercians, pp. 372, 373.

13. Barakat, Cistercian Sign Language, p. 25.

14. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (text in French and English) (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996), p. 11.

to the artist: "You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. L. Aubry, Abbaye de La Trappe, (Rouen: C.R.D.P, 1979), pp. 3, 4, 5.

3. L'Abbaye Notre Dame de la Grande-Trappe, authored anonymously by a monk of La Trappe (Orne: Montligeon, 1926), pp. 65, 76, 78.

4. Louis J. Lekai, The Cistercians, (Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1977), pp. 188, 189.

5. Psalm 119 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 118 in the Vulgate.

6. Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1962), The Community Rule, pp. 97-123.

7. Philo of Alexandria, The Contemplative Life and selected writings, translation by David Winston, (Paulist Press, New York, 1981), pp. 41-57.

8. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, translated by Norman Russell, (Oxford: Mowbray, and Michigan: Cistercian Studies, 1980), pp. 111, 112, 134.

9. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the Vulgate Bible numbering of the Psalms.

10. The Lives of the Desert Fathers, pp. 3, 65, 106, 114, 115, 149, 155.

11. Robert A. Barakat, Cistercian Sign Language, (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1975), p. 24.

12. Lekai, The Cistercians, pp. 372, 373.

13. Barakat, Cistercian Sign Language, p. 25.

14. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris, (text in French and English) (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996), p. 11.

Presented here, (fig. 9), is a superb oil on canvas painting entitled Frère Samuel, Portrait of a Trappist Monk in Prayer. The bold abstraction of the white cowl is in striking contrast to the chiaroscuro modeling of the face of the monk, his head inclined and his eyes lowered as he prays. Roseman has expressed the intense spirituality of Frère Samuel in this masterly rendered portrait.